Art of Dying

(George Harrison)

From the George Harrison album All Things Must Pass

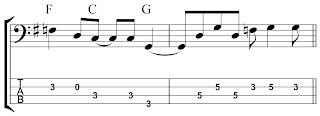

Radle’s bass line on “Art of Dying” is, characteristically, simple, repetitive, and supportive. The song begins with a 4-measure guitar intro. The band comes in at measure 5 with a descending melodic line over an A minor chord. Radle keeps this anchored by repeating the same one-measure riff six times until the harmony finally reaches an E7 chord.

On the verses, Radle plays primarily on the off-beats. His line is mostly root notes, with occasional passing tones, but the syncopation, accenting the “and” of each beat, builds a great deal of tension. This tension is finally released when he settles into a more regular rhythmic pattern in the last four bars of each verse, once again emphasizing the beat rather than the off-beat.

Radle makes a mistake in the transition from the end of the first verse into the second, landing on E on the downbeat of m. 33 instead of A (at approximately 1:00 in the recording). He quickly leaps up to A, but doesn’t reestablish his syncopated pattern until m. 34. It seems that little slip threw him off for a second, because he makes another mistake in m. 35. Just looking at the transcription, or even playing it, nothing seems wrong. But if you listen to Carl in the recording, he hits that G on the “and” of beat 2 and releases it suddenly and awkwardly. It’s not really a bad note, it just seems like it wasn’t what he meant to play.

Those little mistakes were certainly not significant enough to render this recording unusable. It just shows that the energy and feel of a performance is more crucial than 100% accuracy. If this had been recorded today, those errors likely would have been fixed in editing, but in the 1960s and 1970s, recording was done on tape. If someone messed up, often it meant that the whole band would have to redo the entire take. Thus, performance mistakes were much more common in recordings in the pre-digital age.

And now, a bit of speculation for fun…

Another item of interest is the groove Radle plays for the interlude in mm. 73-78 (starting at approximately 2:15 in the recording), which uses the same progression we heard in the intro. Radle again plays a one-measure pattern, but it is different from the line he played in the intro. This may not seem significant, but it is actually extremely atypical for Radle. In a section like this, usually he would have a set line he is going to play, and play it the same way each time that section appears. This alternate groove sticks out and makes me wonder if it was a mistake and he just went with it, or if he was still experimenting with the bass line and was just trying out a different option.

The latter scenario seems somewhat difficult to believe. The rest of this bass line has been worked out so well. His line on the bridge (mm. 53-68) is carefully constructed, to the point that it is being doubled by a guitar. Even comparing the last four measures of each verse (mm. 29-32, 49-52 and 97-105), a section that would lend itself to improvisation, Radle is very consistent in what he plays. So what happened in these other spots?

This alternate groove in mm. 73-78, along with the minor stumbles in mm. 33-35, are interesting artifacts in Radle’s playing. Mistakes in and of themselves are not interesting. Everyone makes mistakes. You can hear mistakes in many recordings from this era. But the alternate groove in mm. 73-78 may not have been a mistake. It may have been a deliberate choice. And while it is an okay choice, it is an unusual choice for Radle. And when studying a bassist’s playing style—as is the purpose of this blog—investigating and questioning atypical choices can help shed light on the typical choices the player makes.